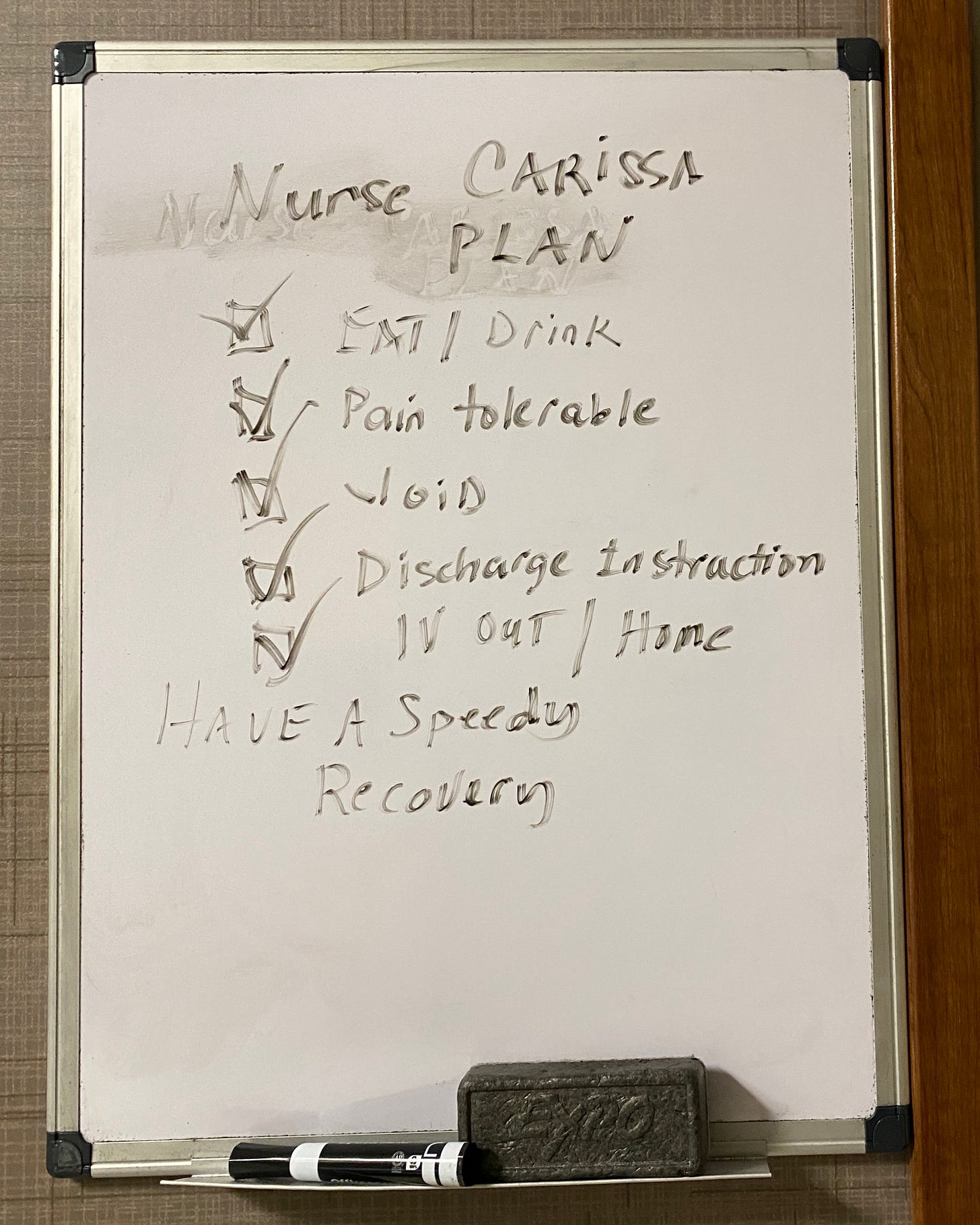

The nurse handed me a cold, plastic bowl that resembled a cowboy hat with measurements marked on the side. There was a whiteboard on the wall of my hospital room with a checklist of steps I needed to achieve before being discharged. Eating and drinking was comparably a breeze, even as the saltine crackers stuck to the walls of my throat, which felt like sandpaper after being intubated. The pain was surprisingly tolerable thanks to the opiates coursing through my IV. The only challenge between these three walls, a thin curtain, and my freedom was voiding my bladder.

All I had to do was piss in a cowboy hat.

Two people grabbed each arm to help me rise from the hospital bed. Back hunched, stomach clenched, every step felt like my insides would slip out from underneath my gown, and splatter onto the linoleum floor. I almost fainted when glancing back at the bed to see a pool of blood in the spot where I had just lied. They assisted me to the bathroom, lowering me onto the toilet seat.

It took three bathroom trips before I could fill up the hat (apparently they’re called graduated specimen collector pans), bearing down on muscles that were sore and painful. On the way home, I asked my friend to stop by a McDonald’s to pee. She escorted me to the stall and ordered McNuggets for us while I emptied myself again.

The ride home took more than an hour due to traffic. My body was tender to the touch and tired from its ordeal, yet there was no discernable pain. In contrast, my mind was inconsolable, just beginning to process everything that was relayed to me about my condition.

“Confirmed stage IV endometriosis. The laparoscopic excision should’ve taken an hour and a half, but it took four hours. It was everywhere, on your bowels and throughout your pelvic cavity. We tried to get everything, but there’s still some left on your uterus and a suspected lesion on your diaphragm. You’ll need to take your birth control every day to prevent further menstrual periods. We need to discuss a long-term treatment plan to address your fertility, tight pelvic floor, and general symptom management.”

On average, it takes ten years to get properly diagnosed with endometriosis in the United States. It took me four months. There were moments when I’d sprint ahead, scheduling appointments, and researching all the possible causes of my myriad of symptoms. I spoke with front desk receptionists between work meetings, repeating my name, address, phone number, date of birth, and insurance information. I’d feel deflated upon hearing that a doctor wouldn’t be available until three months out. The appointments I did manage to book were dismissing, sending me into a spiral of questioning whether this journey was worth the immense mental and physical exhaustion.

I’ve never been in denial of my situation, but I’ve found myself oscillating between the stages of acceptance and crippling depression. There are weeks when I’m feeling hopeful for my future, simply allowing the disease to coexist like a benign tumor hanging from my side. There are days, even as I’m writing this, where I’ll crumple into a ball on my bed, sob uncontrollably, and stain my silk pillowcase with tears.

Much like Nurse Carissa wrote on the board, I had to empty myself of everything and seemingly start anew. This disease has cost me almost everything: the ability to care for a beloved pet, a long-term relationship, the ability to exercise freely, three races I signed up for and had to skip, thousands of dollars in medical bills, and most of all, my sense of self.

There are times I look in the mirror and don’t recognize the person staring back. Her high cheekbones are the same, perhaps a bit fuller. Her brown skin still shines in the sunlight. Her locs have grown past her shoulders. Her stomach is a bit rounder, with four small scars that are gradually fading each day. The baggy jeans she bought last year now fit just right and her sports bra presses tighter against her ribs. She carries the weight of this diagnosis on her shoulders and, according to others, she carries it well.

Her therapist, sympathizing from across a screen, says she’s doing a great job coping with the news. Her pelvic floor therapist, with a gloved finger inside, says she’s healing well. Her surgeon, casually suggesting a hysterectomy before the age of thirty, says she’s doing a great job taking her medication every day. Her friends, offering her their unwavering support, keep telling her that she’s strong.

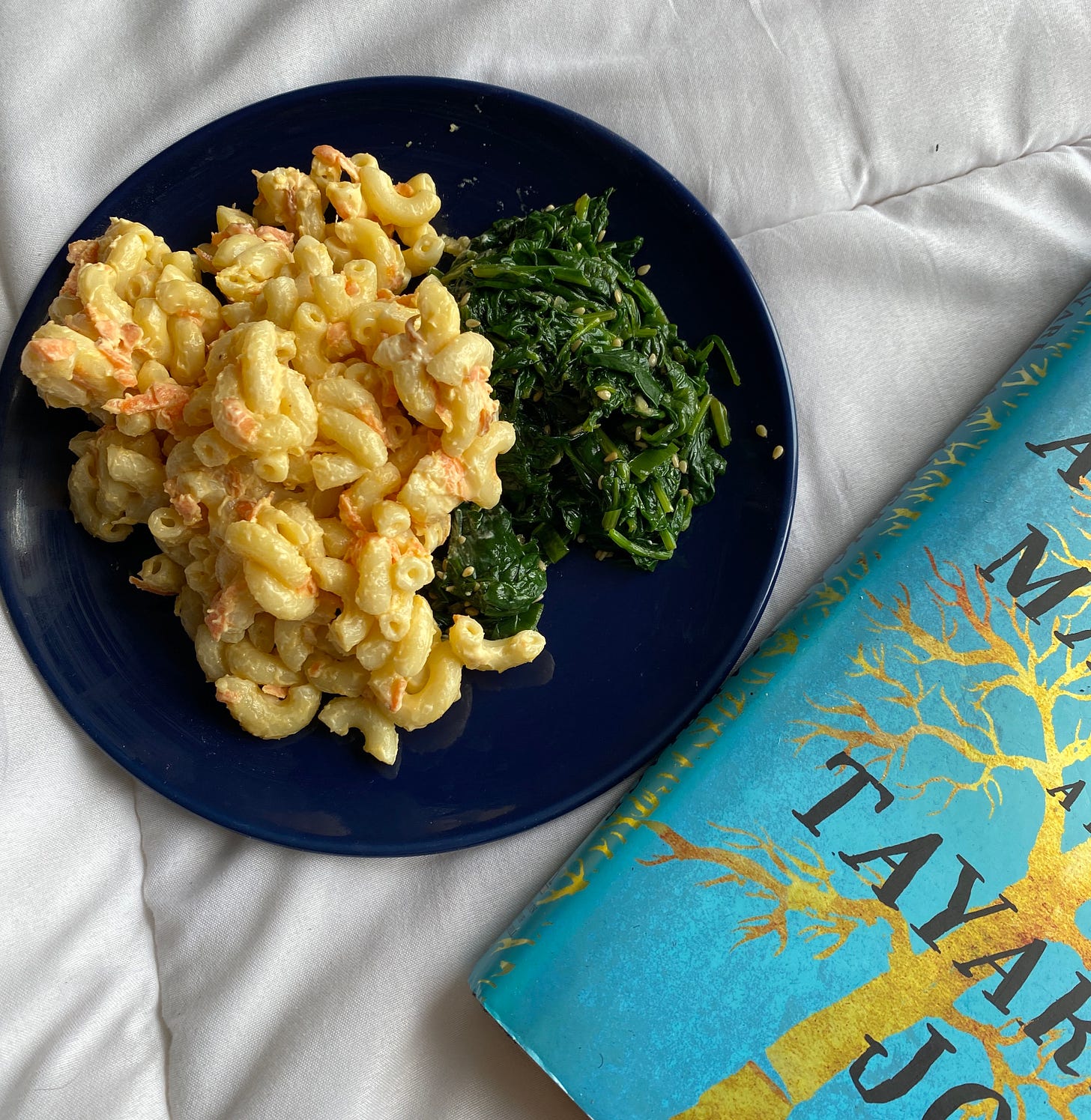

Not much cooking is being done this week due to a lot of life transitions going on. I have limited time in the kitchen these days. I typically end up cooking a large batch of food, freezing half of it, and eating the rest over the next few days. Hawaiian macaroni salad and sigeumchi-namul provided me sustenance for most of the week. Sometimes you just need some good old-fashioned comfort food.

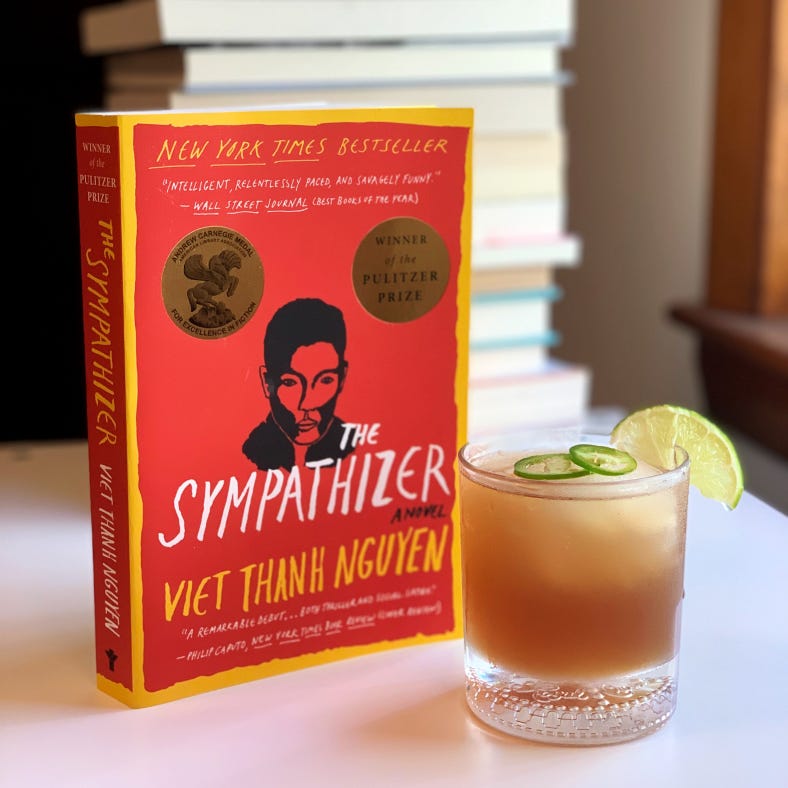

I picked up The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen at a bookstore in San Francisco back in January and quickly got through 100 pages. Since then, my attention has been stolen by a growing collection of cookbooks! This past week, I picked The Sympathizer back up and fell in love all over again with this novel. It’s told from the perspective of a French-Vietnamese Communist double agent living in the Los Angeles area following the Fall of Saigon.

While the narrator was referring to something completely unrelated to my life, this particular quote from the book spoke to me.

…while pain is universal, it is also utterly private. We cannot know whether our pain is like anybody else’s pain until we talk about it.

I’m letting that sink in today as I send out this newsletter for strangers to read. My pain is personal, but by no means should it be private. I hope at least one person can find solace in my story.

Good news: Slow Simmers is a free-for-all publication! But if you enjoyed this post, you can support my writing, amateur iPhone photography, and entertaining recipe attempts by subscribing below.